The Book

SENSE OF AGE

Richard Wiener has always been interested in the changes that time brings. In his book, Sense of Age, he reflects upon the realities of life throughout a person’s lifetime, both prospective and retrospective, in words of rhythm and rhyme. With this book, the author hopes book readers will be inspired to take an honest look at their past, present and future.

AN OLD FRIEND DIES

An old friend dies,

And it’s as though an ancient bridge

Connecting our two worlds collapsed.

One more who knew us when we were still young

One more who shared our memories,

Who validated our past, is gone.

A mirror that reflected back to us

An image of perpetual youth

Has shattered, and mere shards

Remain. In that one instant,

We take an onward leap

Into the vision of our own demise,

Perhaps unconsciously wishing

To see our friend again.

September 3, 2016

SENSE OF TIME

My life has been a journey from victimhood to life affirmation. A child survivor of the Holocaust, I lived for six years under the Nazi regime, and, as the only Jew in my school, was harassed by my Hitler Youth classmates on a daily basis. In November 1938, my father was shipped off to concentration camp, and I witnessed the destruction of my home by Nazi thugs. A few months before the outbreak of World War II, I escaped to England with the famous Kindertransport and, when the bombs began falling on London, I was evacuated with my school and lived for a year with an English foster family. In 1940, at the height of the Atlantic U-boat campaign, I sailed for New York with my parents. After service in the U.S. Army, I worked my way around the west at hard labor jobs, then studied at Columbia and Princeton, and ultimately became an international patent lawyer. My original ambition, to become a novelist, was not fulfilled.

With a unique charm and bearing, Wiener’s refined brand of poetics, Sense of Time, will spark the imagination and infuse the heart and senses.

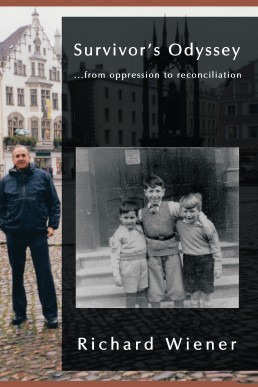

SURVIVOR’S ODYSSEY

As I sit by my window, gazing out over the autumnal park, the turning leaves straining in the gusting west wind, and a suggestion of morning sun stippling a clump of trees in the near distance, my thoughts return to the view from my childhood room on Lutherstrasse, a bourgeois, cobblestone-paved street in Wittenberg lined with neatly spaced lindens.

How tranquil it all seemed then. Like other early childhoods contemplated late in life, mine seems idyllic in retrospect. A cozy home, devoted parents, playmates and relatives nearby. Who could have predicted then that Wittenberg, this ancient town, the cradle of the Protestant Reformation, would soon, like the rest of Germany, be swept up in the fanaticism and hysteria of National Socialism?

When did I first realize that I was not just another German child, that I was merely tolerated, later reviled, and finally cast out? How strange it seems now that it took so long for me to comprehend that what was happening to me and my fellow Jews was extraordinary.

Finally, in November 1938, all the accumulated hatred reached critical mass. And the dry tinder was ignited by an assassin’s bullet. The son of Polish Jews, enraged by his parents’ deportation, shot an attaché at the German Embassy in Paris, and this provided a sufficient pretext for what came to be known as Crystal Night (Kristallnacht), the opening salvo of the Holocaust. The official story was that the assassination so outraged the German people that they could not be restrained from seeking revenge. The truth is that, in a clearly coordinated effort across the entire country, synagogues were set afire, Jewish shops looted and destroyed, and Jewish homes invaded and destroyed. A mob mentality nurtured for years had, at long last, found its focus in action.